Andriy Ignatov, 40

Economist, Kyiv

![]() My grandfather always wanted to write our genealogy. So when he died, I decided to do it for him.

My grandfather always wanted to write our genealogy. So when he died, I decided to do it for him.

I think a lot of Ukrainians are thinking about their personal history these days. We're all wondering how to deal with this legacy that's been handed to us -- communism, famine, World War II, Orthodoxy. It all feels very fresh, very raw, now that Russia is waging war on us again.

![]()

Yuriy Ignatov, Kharkiv, 1936

In Ukraine, your hometown says a lot about who you are. Every city has its own distinct character. "Oh, you're from Vinnitsya? You must be this kind of person," etc.

My grandfather, Yuriy Ignatov, grew up in Kharkiv, and it played a big part in shaping who he was. Kharkiv was the first Bolshevik capital of Ukraine, and my grandfather was a true Soviet.

He joined the Communist Party after World War II and it really gave him education and career opportunities that he wouldn't have had otherwise. He and his wife were veterinarians, and eventually he became a fairly high-ranking agricultural official.

He wasn't a rah-rah communist -- one of those people who got excited by Soviet slogans or getting their pictures taken next to statues of Lenin. He just genuinely believed the U.S.S.R. had been formed for a reason, and that it was out to achieve something important. He took it seriously.

![]()

Yuriy and Andriy Ignatov, Zaporizhzhya, 1979

My grandfather loved to read and learn new things, and he was always ready for an argument with us kids.

I think I was his favorite, because I was the best listener. But we would always talk back. He would tell us about how great the Communists were, and we would tell him it was all bulls--t.

He never agreed with us, but he was always interested in what we had to say. I think we were like a little release valve for him. We said the things that he might have been thinking, but would never have said out loud.

![]()

Yuriy Ignatov (seated) with his family in the outskirts of Kharkiv, 1932

For years, he denied that there had ever been a Holodomor -- Stalin's man-made famine aimed at forcing Ukrainian peasants off their land and onto collective farms. This was true even though his own family had been evicted from their property during the famine. Most of his family died during the famine and World War II, but it was something he never talked about.

Towards the very end of his life, he received a letter from a cousin whose family had been exiled to Arkhangelsk in 1930 because they refused to pay a tax on their sheep. They had managed to come back to Ukraine a few years later, but it was during the famine and they ended up leaving again for good.

So all these years later, here was this cousin living in faraway Arkhangelsk who knew all about the Holodomor, talking to my grandfather who lived right in the famine zone and didn't. Or pretended not to.

I think after that, he started to acknowledge more openly that the system had a lot of problems.

![]()

Yuriy Ignatov's maternal grandparents, Oleksandra and Tymofiy Hrinchenko, circa 1910. The couple had their house and possessions confiscated by Soviet authorities in the fall of 1930 after failing to pay tax on eight sheep. Their eldest son was later sent to a labor camp in Arkhangelsk after refusing to turn over a horse to the local kolkhoz, or collective farm.

Two of his four children died within a year of arriving in northern Russia.

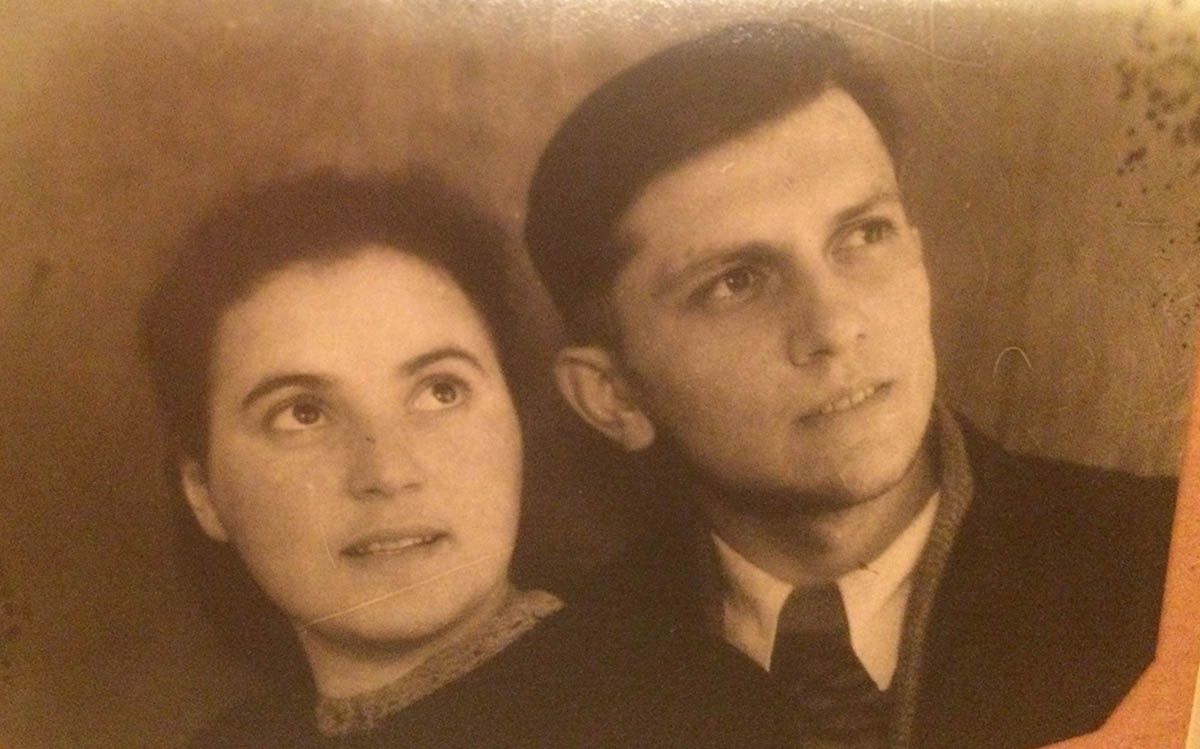

Left: Yuriy Ignatov, Germany, 1946 / Right: Lidia Pryhodko, circa 1949

My grandfather served in World War II and was injured in Kaliningrad. After the war, he was wearing his military uniform when he went to register at the veterinary institute in Kharkiv, and that's where my grandmother, Lidia Pryhodko, saw him for the first time. She said she noticed him because his medals were jingling as he walked down a flight of stairs, and she decided then and there, "That's my man."

A few years ago, someone broke into his flat and stole his medals. He was really upset about that. At that point, the Soviet Union had collapsed, Ukraine was independent, and the rules as he knew them were changing. He couldn't believe that someone would steal his World War II medals. "There should be some order!" he said.

We told him to go to the police, but he refused. He had heard so many stories about corruption, he thought the police would just accuse someone in the family of stealing the medals as a way to extort money from us.

![]()

Oleksandr Ignatov in the laboratory of the Kharkiv psychiatric hospital and research institute, 1938

There are a lot of doctors in my family, and a lot of psychiatrists.

My great-grandfather, Oleksandr Ignatov, was in charge of running the Kharkiv psychiatric institute during World War II. Communist Party members were evacuated ahead of the German advance, because they were considered at high risk of execution. My great-grandfather wasn't a Communist, so he stayed behind.

At some point, the Nazis came and executed the patients, more than 400 people. There was some speculation that my great-grandfather tried to kill himself, out of fear or despair. But we don't know if that's true. In any case, he remained in the profession for the rest of his working life.

My father is also a psychiatrist, and my maternal grandmother was as well. She was the director of the regional psychiatric clinic in Zaporizhzhya, where Crimean Tatar dissident Mustafa Dzhemilev was sent for evaluation when he was jailed in the 1970s.

I always believed that Ukraine didn't use punitive psychiatry the way that Russia did. Or perhaps we did, but only in Kyiv. But these are the kinds of questions we need to be asking ourselves now.

![]()

Yuriy Ignatov (second from right), Zaporizka Oblast, 1965

Despite being a real Soviet man, my grandfather was also an intellectual and very proud of being Ukrainian. He saw Ukraine as the engine that kept the whole U.S.S.R. running.

Occasionally you could hear him joke about how incompetent Moscow bureaucrats were, or grumble about how unfair it was that Ukraine produced so much grain and metal for everyone else and got so little in return.

And as he got older, he began to see that his children weren't enjoying the same benefits that he had. Factory workers were making more than doctors. Life wasn't getting better.

He was also intolerant of other types of Ukrainians -- he didn't like Poles or Tatars at all. Publicly, he subscribed to the Soviet "brotherhood of nations," but in reality he thought Sovietized, Russian-speaking Ukrainians were superior to everyone else.

He was 87 when he died in 2013. A few months before that, he told me there were rumors in his veterans' group that Russia was going to try to restore the Soviet Union. He thought that would be a good thing.

But I think it would have killed him to see what's going on now, watching Russia invade Ukraine, seeing what these terrorists are doing to us now.

![]()

Areta Kovalsky, 30

Advertising manager, blogger, Lviv

![]() I'm Ukrainian-American, but I moved to Ukraine a few years ago. Lviv used to be my ancestral home. Now it's my permanent home.

I'm Ukrainian-American, but I moved to Ukraine a few years ago. Lviv used to be my ancestral home. Now it's my permanent home.

I'm pretty passionate about researching my family history. It's great to be here in Lviv where I can find old records and gravesites and in some cases even distant relatives.

My family is lucky in that we've held on to a lot of our photographs. One of my favorites is one of the oldest, from the early 1900s. It shows my great-great grandparents with some of their children and nieces and nephews.

![]()

Yosifa Kuhn-Bednawska and Leon Bednawski (seated center), photographed with their children, nieces, and nephews, early 1900s

I think it's a very interesting picture because it shows a good portrait of life in Galicia, the territory that comprises parts of modern-day western Ukraine and southeastern Poland, where people of different ethnicities and religions lived together pretty harmoniously.

My great-great-grandfather, Leon Bednawski, was Polish and Roman Catholic. My great-great-grandmother, Yosifa Kuhn, was Ukrainian and Greek Catholic.

At that time it was common for Poles and Ukrainians to intermarry, but they tried to preserve both cultures at home. It was traditional for the sons to be brought up in the religion and language of the father, and the daughters brought up in the mother's.

Several of Leon and Yosifa's children died young, and in one instance a son and a daughter shared a gravesite. The son's plaque is in Polish, the daughter's in Ukrainian. It's a custom that had really interesting consequences in this part of the world, where borders and nationalities kept changing.

![]()

Ivanna Bednawska (top right) with two aunts and her uncle, Toma Dutkevych, Italy, 1908

I love this picture because of the hats. But it's also interesting because it shows the kinds of perks that relatively well-off Galicians enjoyed at the turn of the century.

My great-grandmother, Ivanna, had lost several of her siblings to either tuberculosis or typhus, and her parents sent her abroad to keep her from getting ill.

She traveled with two of her aunts and an uncle. The uncle, Toma Dutkevych, was a parish priest in Chishky, near Brody. But he was also pretty prosperous because he was a very successful farmer.

He and his brother helped create the Silskiy Hospodar movement, which promoted modern farming techniques. It was part of the same cooperative movement in Galicia as Prosvita and Narodna Torhovla, which helped improved education and trade.

Toma had a big library and was friends with Ivan Franko, the poet and activist, who would come to borrow his books.

![]()

Bohdana, 19 (left), and Maria, 12, in 1931

Ivanna had two daughters: my grandmother, Bohdana, and her sister, Maria. They were born near Przemysl, which is now in Poland, and grew up in Brody. They were separated during World War II. They didn't see each other again for almost 50 years.

My grandmother had already been arrested once for her ties to the Ukrainian nationalist movement, which was active in Galicia. When the Soviets resumed power after the war, she knew she had to get out of there before she was arrested again.

Bohdana fled with her husband, their baby, her mother, and her grandmother, who was already in her 90s. (Amazingly, her grandmother -- my great-great-grandmother, Yosifa -- survived the journey. She died in Michigan in 1951.)

They couldn't find Maria before they left. She was in Brody, which had come under heavy bombardment. She had joined the UPA, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, the partisan army fighting for an independent Ukrainian state. In 1946, she was arrested.

![]()

Maria being held above the water, Brody, 1936

Maria spent 10 years in prison in Mordovia, and another five years in exile in Krasnoyarsk.

Eventually she came back to western Ukraine. She even wrote a book about her life as a partisan. But it was years before she knew what had happened to Bohdana and the rest of the family. They didn't see each other again until 1990.

I spent time at Euromaidan, and Lviv has had its own unrest over the past year. At this moment in Ukraine's history, I can't help but think about my ancestors and how they must have felt during World War II and the partisan struggles to liberate Ukraine.

I feel very close to them, being here.

![]()

"During World War II, the Russians really hated us for living under occupation.

And now they're using it against us again, calling us Nazis and fascists."

Mykola Chaban, 56

Journalist, ethnographer, Dnipropetrovsk

![]() Everyone in Ukraine has an interesting history. I've researched so many families -- my own and other people's -- and it's always fascinating.

Everyone in Ukraine has an interesting history. I've researched so many families -- my own and other people's -- and it's always fascinating.

My great-grandparents, Martyn Harzha and Vustya Horpyna, are a case in point. Vustya was pure Ukrainian, but my great-grandfather was a Vlakh of Romanian origin. They were peasants, and they had two horses. This made them relatively prosperous for the time.

These horses caught the eye of the Makhnovshchina, the Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine. They kind of promoted themselves as Ukrainian Robin Hoods. Stealing from the rich, giving to the poor, that kind of thing. Very fair-minded. So when it came to my great-grandfather's horses, they didn't steal both -- only one.

My great-grandfather was very angry, and he marched off to talk to the group's commander, Batko Makhno. Everybody feared the worst. Martyn made the case that he wasn't actually all that rich, and that he really needed the horse back.

The horse was returned. Occasionally Batko Makhno liked to make those kinds of magnanimous gestures.

![]()

Martyn Harzha and Vustya Horpyna, early 1900s

Martyn died of Spanish flu in 1919; Vustya died of starvation during the Holodomor, Stalin's forced famine. She went to a hospital for help, but they just said, "You don't need medical help. You need food." They left her lying on a sheet on the floor to die.

Their daughter -- my grandmother, Yevdokia -- survived the famine, but her life was very hard. She and her husband Andriy worked on a kolkhoz, a collective farm, in their village of Mayorka. But then Andriy was arrested for reciting a rhyme about Stalin. "Spasibo Stalinu-Gruzinu, za to chto obul nas v parusinu i rezinu." Thank you, Stalin the Georgian, for giving us shoes made of burlap and rubber.

It was just a little joke about shortages, but it didn't go over very well. My grandfather was sentenced under Article 58, the article on anti-Soviet propaganda.

Andriy was sent to the Solikamsky labor camp in the Urals. He died later the same year. They said he died of a heart condition, but that was their politically correct way of putting it. We found out later he died of pellagra, which is caused by malnutrition. A lot of people in the camps died of that.

![]()

Petro, Andriy, Lidia, Yevdokia, and Mykola Chaban (left to right)

I was named after my Uncle Mykola. He became the man of the house when he was 14.

My grandmother and her three children made it through the German occupation, but during the Lower Dnieper Offensive in autumn 1943, when Soviet troops were pushing the Nazis back west, Mykola was forced into military service. He was killed almost immediately. He was 17.

He hadn't been given any kind of training; he didn't know how to defend himself. Stalin wanted to liberate Kyiv on the anniversary of the October Revolution, and he was pushing the Soviet Army as hard as he could. That caused a lot of unnecessary bloodshed.

![]()

Mykola Chaban (left) and his boyhood friend Vanya Zaskoka

My uncle was killed about 20 kilometers away from Mayorka. When my grandmother heard the news, she walked to the spot to find him. His body had been thrown in a mass grave. But she was able to identify him.

She had given him a scarf, a spoon, and some meat pies before he left. He still had them with him -- that's how quickly he was killed.

The military officer there said she was free to take the body away, but she had no way to carry it. She walked back to her village to see if she could borrow a horse from the kolkhoz.

They refused, because they were afraid the Soviet military would just make off with a horse. But they allowed her to take a cow. So she walked back to the mass grave with the cow, and then slowly pulled Mykola's body home so she could bury him in Mayorka.

![]()

Lidia, Yevdokia, and Petro Chaban, Baku, 1948

So within a decade, my grandmother lost her mother, her husband, and her oldest son.

After World War II ended, there was a second wave of famine in Ukraine, so my grandmother took her two remaining children -- Lidia and my father, Petro -- and moved to Azerbaijan.

They packed three small suitcases; one of the suitcases was stolen on the train. But they made it to Azerbaijan, where they could at least earn enough to buy food.

My father started his army service after this, and served in Armenia. He was not impressed by military life in any way. He still hates when veterans put on all their medals and walk around. To him, the real soldiers were the ones who were killed or injured.

After Stalin died in 1953, they felt like it was safe to move back to Ukraine. But their farming life was already over. They settled in Dnipropetrovsk. My father found work in construction.

![]()

Mykola and Yevdokia Chaban (second and third from left) at the cemetery in Mayorka

While my grandmother was still alive, we went to visit Mykola's grave on a regular basis. She died in 1994, when she was 87. She's buried next to him now.

People here are very tough. We've been through a lot. It's very common for older women to say, "I can endure anything, as long as there's not a war." So it's very painful to see what's going on now in Ukraine. We know what war is, and it's horrible.

![]()

Anastasia Aslanova with her husband, Mykhaylo Byelosotskiy, standing outside Independence Square. "During the Maidan, it was much scarier to stay at home than go to the square. At home, you were on your own. At the square there was something to do."

Anastasia Aslanova, 31

Product manager, Kyiv

![]() A lot of people see my surname and think I have roots in the Caucasus. Actually, it's a Turkic Greek name. Catherine the Great brought a lot of Greeks to Crimea after defeating the Ottoman Turks, to get more Orthodox Christians into the region. Both of my father's grandfathers were Greek Ukrainians. They lived in Mangush and Starobeshevo, near the Azov Sea, where a lot of Greeks resettled after living in Crimea.

A lot of people see my surname and think I have roots in the Caucasus. Actually, it's a Turkic Greek name. Catherine the Great brought a lot of Greeks to Crimea after defeating the Ottoman Turks, to get more Orthodox Christians into the region. Both of my father's grandfathers were Greek Ukrainians. They lived in Mangush and Starobeshevo, near the Azov Sea, where a lot of Greeks resettled after living in Crimea.

Stalin, as we know, liked to play with nationalities. He wanted to destroy Ukraine as a nation, so he started by starving people to death during the Holodomor. Then he deported the Crimean Tatars to Central Asia and started getting rid of the Greeks, as well.

One of my Greek great-grandfathers, Timofiy Aslanov, was taken away in a black car and never came back. Just a few years ago, I found a document that said he had been executed. In the space where they give the reason for the execution, someone had written: "Greek." That's it.

![]()

Timofiy Aslanov, circa 1901

My great-grandfather's arrest was quite hard for his family. It was never good to be related to an enemy of the state. My grandfather, Arkadiy, was well aware of this, and when World War II began, he tried to get drafted into the Soviet Army.

He was only 15, but he ran away from home and lied about his age, hoping that if he served in the military it would somehow help him and his family.

It didn't work, though. They figured out how young he was and wouldn't let him enlist. So he had to go back home, and that made things even worse, because if you stayed in Ukraine under the German occupation it was easy to accuse you afterward of being a collaborator.

![]()

Varvara Aslanova with her three children (from left) Arkadiy, Halyna, and Yevhen, circa 1939

To make matters worse, one of their neighbors reported that Arkadiy had drawn a picture of Hitler with his finger in the fog on a window. That was all the proof they needed that he was a Nazi sympathizer. He was arrested and sent to a labor camp in the Far East for 10 years.

It was there that he met my grandmother, Emma, a nurse in the labor camp. She was also from Ukraine, from Odesa. Her father was Jewish and her mother was Bulgarian.

Her story is a little like Arkadiy's. During World War II, she had also run away from home. Her mother had died and her father married a woman who was abusive to Emma and her brother. She burned her passport to hide her age and volunteered to serve as a surgical nurse. She was 16.

![]()

Emma Vainshtein with her mother and brother, Yan, Odesa, 1932

They wanted to send her to the Japanese front, but she only made it as far as the Far East. She was able to earn a pretty good living there, and she had some special privileges. When she met my grandfather, she was able to provide him with a double ration of food. I'm sure it was still nothing, but it probably helped keep him alive. It was very cold and damp there.

My grandparents never talked about life at the prison camp. Never. Even my father refused to talk to me about it. He would always joke and say that those old stories were boring. It took a long time to hear those stories. I realize now they were trying to protect me. They were afraid that if I knew the truth that it would put me at risk as well.

They had a few photos from the camp, but they never talked about the people in the photos, or wrote to them. This kind of fear lasts for decades. You can't imagine living inside this strange world, where you can't trust anyone, and any day they might take you away because somebody once drew something on a window.

![]()

Arkadiy Aslanov (right) performing at a magic show with a fellow gulag prisoner, circa 1946

My grandparents were eventually allowed to come back to Ukraine. But their lives were always going to be compromised by the fact that Arkadiy was the son of an enemy of the state and had served time in the gulag for collaboration.

They weren't allowed to live in a big city, for example. They spent one night in Dnipropetrovsk, at the home of a relative. But after that they had to get on a train and go outside the city. They had two suitcases and an 8-month-old baby.

They got off at Novomoskovsk, about 30 kilometers outside Dnipropetrovsk. It was winter. My grandparents always remembered getting off the train and standing on the platform, looking up at the moon -- there was a very big moon that night -- and thinking, "OK, what now?"

![]()

Emma and Arkadiy Aslanov, circa 1950

My grandfather had learned how to paint at the labor camp, and he found a job painting Soviet art for a local factory. You know, portraits of Soviet leaders, posters for Soviet holidays or Communist Party congresses, that sort of thing. Not exactly what he wanted to be painting.

In the 1990s, the factory newspaper printed an article saying, "The honest name of Aslanov has been restored." He had been officially rehabilitated.

Almost everyone in the former Soviet Union has a story like this in their family. So when the truth finally started to come out, we thought for sure that people would never let history repeat itself. In Ukraine, people are pretty much united in thinking of Stalin as a monster. So it's shocking to realize that Russians really like Stalin! They think he did good things, and they want those things to happen again, to their country and all the countries around them. I have relatives in Russia that I can't even talk to anymore.

We were surprised by Euromaidan. After the Orange Revolution, people sort of had the idea that those protests wouldn't work anymore. But the Maidan was very organic. And once police started beating students, it was enough to make the whole country go crazy.

I think the future in Ukraine will be great. The question is when.

![]()

Volodymyr Ogloblyn, 60

Photographer, Kharkiv

![]() I was a Little Octobrist, a Young Pioneer, a Komsomolets, the whole deal. But I never got into the Communist Party. I was the type of person who asked too many questions. It didn't kill me professionally, but it did make things a little bit harder.

I was a Little Octobrist, a Young Pioneer, a Komsomolets, the whole deal. But I never got into the Communist Party. I was the type of person who asked too many questions. It didn't kill me professionally, but it did make things a little bit harder.

Technically, I'm Russian. My parents were Russian and I've spent a lot of time there. But I've lived in Kharkiv since I was small and this is my city. Ukraine is my country. It's never been otherwise.

I was raised by a single mother. She worked for the post office. My father was in the army and then just kind of drifted off. He ended up marrying another woman with the same name and patronymic as my mother. Maybe it made things easier for him -- less to remember.

![]()

Volodymyr holding the dove, with his mother in the white hat standing behind him, May Day, 1962

We went out to the square for all the Soviet holidays. No matter what. You had to, otherwise someone would call the police.

When I was about 14, my mother and I went to Crimea for the first time. It was the first time I had seen the sea, and it was amazing.

What Putin did in Crimea is no different than taking someone's wallet. He stole Crimea from us.

![]()

Volodymyr with his mother, Crimea 1968

I spent a lot of time doing sports growing up, mainly cycling and running. Eventually that gave way to studying. A lot of my pictures from that time are fairly idiotic.

![]()

Archaeological expedition, Dnipropetrovsk Oblast, 1972

I've backpacked through Kazakhstan and other parts of Central Asia. And I've been on dozens of trips to Russia.

In 2001, I accompanied a group of Russian explorers to the Arctic. The trip was led by Vladimir Chukov, a very well-known polar explorer.

We spent two months in the Franz Josef Land archipelago, hiking from one island to another over the ice. I was the only Ukrainian in the bunch, and the only photographer.

Being Ukrainian was fine, but being the photographer was a nightmare. It was minus 57 Celsius and none of my cameras worked. I ended up having to fall back on an old mechanical film camera. It was the only one that didn't freeze up.

![]()

Volodymyr and Vladimir Chukov (second and third from left)

The team was 17 kilometers from the starting point and about to make their first venture onto the ice.

We had to carry carbines because of the polar bears. At some point a bear stole my backpack, but I got it back.

I usually travel with a gun, because I spend a lot of time in remote areas with wolves or bears. That's something that's gotten harder in recent years, traveling to Russia and trying to explain what you, a Ukrainian, are doing there with a gun.

There are an amazing number of abandoned planes all over Franz Josef Land.

![]()

Volodymyr in Franz Josef Land, 2001

Most recently I've traveled to the Far East and Magadan to work on travel books. Ukraine is beautiful, but of course it doesn't have the geographical range that Russia does. I've been to some incredible places in Russia.

I've worked for years with Russian publishers, but it's not clear those relationships are going to continue. It's tough to have a normal conversation with Russians these days.

For one thing, they're blind to what's going on in Ukraine. And for another, they can't bear the thought of Ukrainians living better than they do. They think that if they live badly, everyone else should, too. And they can't stand the fact that Ukrainians on the Maidan were ready to die for their country.

We are spiritually free. And they aren't.

They love to say Russia is a great country. I always tell them it's not great -- it's just big.

![]()

School trip, Dnipropetrovsk, 1972

We got Yanukovych out. Now we just need time to help the country grow -- 10, 20, 30 years.

Ukraine has everything it takes to be a great country. There's fertile land, great tank and navigation technology, great institutes for physics and chemistry.

We need time and money. But all the money we could be investing in Ukraine, in our country, is just being spent on this bulls--t war that we were absolutely not ready for.

The hospitals in Kharkiv are full of wounded soldiers -- from both sides, by the way. I collect clothes for some of these guys. They literally have nothing, these boys. People donate money to pay for their operations and artificial limbs.

Just let this war be over. We've got a lot of work to do!

Natalia Zubchenko, 31

Anesthesiologist, Dnipropetrovsk

![]() A few years ago I became interested in my family heritage because I'm the last in my line, and because there are very few members of my family still alive.

A few years ago I became interested in my family heritage because I'm the last in my line, and because there are very few members of my family still alive.

All in all, there are really just four of us -- me, my mother, my grandmother, and my mother's cousin. We're all doctors by profession.

I work as an anesthesiologist at the front-line evacuation hospital set up at the Dnipropetrovsk State Medical Academy for wounded Ukrainian troops. My husband is also an anesthesiologist; he's currently working in a field hospital.

Most of us didn't have any experience with field medicine or treating combat injuries, of course. We weren't expecting a war. It took us about two months to get up to snuff.

![]()

Natalia Zubchenko's grandmother, Nina Holovakha (center row, seventh from right), with fellow first-year students at Dnipropetrovsk State Medical Academy, 1950s

In Ukraine, we say we have a traditionally matriarchal society. Even in the Middle Ages, it was the groom who would come to live with the bride's family, not the other way around. It's very customary for women to work as doctors.

My grandmother, Nina, was born in the village of Chervone in Zaporizka Oblast. It was 1933, in the middle of the famine. There were five children altogether.

My great-grandparents had already been labeled as kulaks -- wealthy peasants -- and had their property seized. My great-grandfather, Danylo Holovakha, had owned a mill. But somehow he and my great-grandmother managed to find work during the Holodomor, and no one starved to death. They ate grass and whatever they could find to survive.

![]()

Danylo Holovakha and his son, Pavlo, in Chervone

My grandmother moved to the city around Dnipropetrovsk around 1950 to start nursing school and then medical school. She became an ob-gyn. People always thought she looked a little like the actress Vivien Leigh.

She never had any particular love for the Soviet Union. Her memory of World War II was of the German soldiers handing out candy and the Soviet ones ramming their tanks into houses.

In 1963, she was formally punished at work for speaking Ukrainian instead of Russian. But she ended up being the Communist Party boss at her hospital just the same.

Now she speaks Russian better than Ukrainian. But occasionally I can still hear the Ukrainian slip in, especially when she answers the phone.

![]()

Nina Holovakha (left) with her mother and sister, 1940s

Dnipropetrovsk is a very specific city. A lot of Kremlin bosses came from here. Brezhnev was born nearby in Dniprodzerzhynsk. Leonid Kuchma, Pavlo Lazarenko, and Yulia Tymoshenko are all from here.

For a long time, it was a closed city because of the Yuzhmash ballistic missile plant. Even now, we have our own way of doing things. We don't think of ourselves as east or west. We're central.

I think Euromaidan did a very good thing for Dnipropetrovsk. If a year ago you had shown someone here a blue-and-yellow flag, I don't think it would have meant anything special to them at all. But the Maidan roused people's sense of national identity.

If the Russians had invaded and there had been no Maidan, I think the situation right now would be quite different. They might have made it to Dnipropetrovsk, or even further into Ukraine.

That said, I don't think our soldiers are getting nearly the support they need. I think there's more to this war than we can see. I only hope that when we find out the whole story, it'll be clear that our people are dying for a reason.

![]()

Pavlo Holovakha (left) during military service with the Black Sea Fleet, early 1940s

I've traveled quite a bit, and I used to spend a lot of time explaining that Ukraine wasn't in Africa or Asia, that it was a country next to Russia, but that it wasn't the same thing as Russia.

Now when I travel, people get really excited when they see my passport. In one country, all of the passport-control workers even passed it around, saying, "Ukraine! She's from Ukraine!"

For a while, I was worried I wasn't going to get my passport back. But it's nice to know that other people know about my country and care about what's happening here.

![]()

Alla and her son, Anatoliy, who spent nearly every day at Independence Square during Euromaidan

Alla Husarova, 47

Journalist, Kyiv

![]() Nearly all of my family comes from the Vinnitsya region, mainly from small villages. Now there are buses that take you to these tiny towns directly, but it used to take hours and lots of waiting and transfers to get back and forth from Kyiv.

Nearly all of my family comes from the Vinnitsya region, mainly from small villages. Now there are buses that take you to these tiny towns directly, but it used to take hours and lots of waiting and transfers to get back and forth from Kyiv.

It really felt far away. But all of Ukraine's 20th-century history touched my family in one way or another.

My maiden name is Bondarchuk. My great-grandfather, Yakov Bondarchuk, grew up as a simple village kid. But he was slightly different in that he had gone to school and learned to read and write. That wasn't the case for everyone back then.

So when the Russo-Japanese War started in 1904 and they began drafting Ukrainians, they singled out the boys who were literate to train as medical assistants. So my great-grandfather didn't fight; he worked in the surgical ward.

![]()

The Bondarchuks (counterclockwise from left):

Yevdokia, Lidia, Yakov, and Ivan, photographed in the city of Gaysyn, circa 1914

It was very difficult work, very emotional, seeing all those injured soldiers. Many doctors from that war became addicted to drugs or anesthesia, since they had such easy access to it. I guess my great-grandfather wasn't an exception.

He eventually was shipped back to Odesa -- a horrible journey in itself -- and returned to his village to become the local doctor. He got married and raised three children, including my grandfather, Ivan. But he remained addicted to drugs, and he died quite young.

My grandfather grew up to become a history teacher and a school director in the village of Bilky. He had grown up in a neighboring village, but he married a Bilky girl, my grandmother, Oleksandra Babukha. Everyone called her Lesia; I called her Babushka Sasha.

![]()

Lesia Babukha (bottom left) at a school celebration in Illintsi, 1925

She was the daughter of an Orthodox cleric who had been forced by Soviet authorities to renounce his vows in order to ensure that his children wouldn't be marginalized. He had 10 children who lived to adulthood, so this was a serious consideration.

My grandmother attended a school specializing in agricultural studies. She went on to teach biology, and botany was her specialty.

She knew everything about plants, and later on in life she kept an amazing garden, with all different varieties of roses and a greenhouse. Visitors were always coming just to look at the garden.

![]()

Ivan Bondarchuk as a young man

My grandfather fought in World War II, as a gunner. He received a certificate of gratitude signed by Stalin for his role in destroying a German tank division somewhere in Hungary or Czechoslovakia.

My grandmother, meanwhile, remained in Bilky during the occupation. She was teaching and living in the school with my father, Valentyn, who was by then a teenager, and his sister, Taisia, who was quite small.

At some point, they had German soldiers lodging with them. One day, my grandmother became frightened because one of the soldiers was sitting and staring at Taisia, who was just 1 or 2 at the time. She was sitting on the floor, playing with a toy, and the soldier was looking at her very intently. But then he started to cry and gave her a sugar cube. He said he had a young daughter at home.

![]()

Lesia Bondarchuk, outside the Bilky schoolhouse

My grandmother didn't harbor any illusions about the Nazis, but she didn't suffer any particular abuse during the occupation either. Terrible things were happening to Jews in Vinnitsya, but life in Bilky was relatively quiet.

When the war was over, the Soviets allowed her to keep her job. She wasn't punished for living under occupation, like many Ukrainians were. But when she retired, she was given a tiny pension -- just pennies. All those years later, they were punishing her for collaboration.

These days, it's really hard to know what was the right thing to do. It's gotten really popular to say your family fought with the partisans. But in Bilky, for example, the partisans weren't up to much of anything good. The people who simply went on living under occupation got a lot of grief, even though the country wasn't doing anything to help them. What could they do? Were they all supposed to flee?

Filip Mospan and Tetyana Honchar, 1930s

My second set of grandparents also lived in Bilky, but they were very different. My grandfather, Filip Mospan, was from a prosperous peasant family that lost everything during dekulakization, when the Soviets forced Ukrainian farmers to give up their private property. They lost their house, their animals -- everything.

My grandfather went east, to the Donbas, to find work. This was during the Holodomor, the famines, and the Donbas was one of the few places where you could find a job and get paid with food. There was a lot of effort going into industrializing the region, and my grandfather spent a few years working in a mine.

It was during that time that he met my grandmother, Tetyana Honchar. She was the daughter of an Orthodox priest who was arrested as part of the Soviet crackdown on religious authorities. He and Tetyana's mother both ended up dying of starvation during the Holodomor.

Tetyana was just a teenager. And as the daughter of a repressed priest, she had been kicked out of school. She never made it past fourth grade. And she refused to recant, which might have helped her get back in the good graces of the authorities. The whole thing left her very bitter.

Filip and Tetyana eventually moved back to Bilky. Filip found jobs here and there, and they worked on their property constantly. That's what I remember as a little girl. With my other grandparents there were books and flowers and walks in the forest, but with them there was just physical work. And religion -- my grandmother remained deeply religious. She tried to talk to me about it, but as a Soviet child, I just found it very strange.

![]()

Babushka Sasha and Alla in Bilky, circa 1970

I lived in Bilky until I was 4. My parents were studying, so they sent me to live with Babushka Sasha. I was her first grandchild, so she loved me a lot. She took me on long walks and taught me everything she knew about plants. Even today I know a lot about nature, about trees and medicinal herbs.

We've always been a Ukrainian-speaking family. I remember coming back to Bilky at some point after I had been going to school in Kyiv and I said something in Russian, to show off a little, you know -- to show that I was a city kid. My grandmother put an end to that immediately.

She died when she was 95, in 2003. She had Alzheimer's for the last decade of her life. But she was always very tidy, very precise. Every night before she went to sleep, she took off her slippers and lined them up very neatly next to the bed. Right until the end.

Oleh Hubar, 61

City Historian, Odesa

![]() I don't identify myself in terms of any kind of nationality or ethnicity. I'm a citizen of the world, if you like.

I don't identify myself in terms of any kind of nationality or ethnicity. I'm a citizen of the world, if you like.

I was baptized as Orthodox, and in the spiritual sense I consider myself a representative of Russian culture. Although, I repeat, I am absolutely not fixated on the issue of nationality.

Odesa is traditionally a Russian-speaking city. Although before the Bolshevik Revolution, of course, it was very common to hear Yiddish -- one out of every three people spoke it.

![]()

My family is like many Odesa families -- a big mix of ethnicities and religions.

My paternal grandmother, Maria Kazakova, was half Jewish and half Russian Orthodox. She was raised in the household of her aunt, who was married to a school-district official in Odesa.

She ended up marrying Lev Hubar, who worked in the office of a milling company with his father and who fought in World War I. The Hubar family was considered part of the Odesa elite.

The last name is derived from the word "guba," which means a long tract of forest. Mushroom hunters are often called "gubars." I'm a huge mushroom enthusiast, so it all worked out pretty well for me.

![]()

Maria and Lev Hubar (both on the right), Odesa, 1916, shortly before Lev left for the front in World War I

My maternal grandmother was also Jewish; my maternal grandfather was a Baltic Sea German.

He ended up deserting from the Russo-Japanese War with a group of other soldiers and went into hiding. He never came back.

We found out later that he had changed his surname from Flaschtatz to Shvartz -- my grandmother's last name -- to help protect his identity. So that was his story. I eventually tracked him down in the archives.

![]()

Oleh Hubar's mother, Yevdokia (far right), Odesa, early 1930s. Yevdokia and her cousin Liza (above right) both survived the pogroms of World War II. The two relatives on the left died in the Odesa ghettos.

My mother, Yevdokia, kept her mother's name as well. She was very distinctive-looking. At school, all the other children called her the Japanese Emperor.

She was lucky enough to survive World War II. Odesa Jews were murdered en masse by Romanians and Germans during the occupation. Many were forced into ghetto settlements and left to die from bombings or exposure.

My mother lost almost her entire family. Her closest relative at that time was her older brother, who was killed in 1943 in the Lower Dnieper Offensive, one of the bloodiest battles of the war. His wife and their children died in the ghetto.

![]()

Iosif Hubar, wearing the Order of the Patriotic War

My father, Iosif Hubar, served in World War II as a senior lieutenant in the Soviet Army. He was decorated after his unit "scattered and liquidated" four German platoons.

My family has always taken a critical stance toward government. But we were never among what I would call the constructive opposition.

We weren't apologists, but we weren't total detractors, either. We always tried to view everything in a rational, sober manner.

Regarding the current situation, I can say that the war isn't being fought in the east. It's certainly not being fought in Odesa.

It's being fought at a much, much higher level. And we -- ordinary people -- are nothing more than bargaining chips in a big game.

![]()

Certification of Iosif Hubar's service in the Soviet Army.

This document allowed his mother to receive special tax benefits and food-supply rations.

It's not worth demonizing anyone in this war, because our leaders are equally bad. Each works for his own interest, and one isn't better than the other. The worst is that so many people are dying because of it.

I've had many opportunities to leave Odesa, to leave Ukraine. All my relatives left. My father, mother, and sister Inna all died in the United States. My uncle and aunt did also. And all their children live there.

I'm all alone here. But I'm a sixth-generation Odesa native. I don't want to leave.

![]()

Yevdokia, Inna, Iosif, and Oleh Hubar swimming in the Khadzhibey Estuary outside Odesa, mid-1950s

Someone needs to stay behind to visit the graves of their ancestors.

And in general, this is my city. I don't need any other. My grandmother is buried here, my teacher, my father's younger sister Olga, in whose honor I was named. And many others. I want to be with them.

![]()

Lucy Zoria with a portrait of her grandmother, Asta, painted by her grandfather, Anatoliy Sumar, at the National Art Museum of Ukraine

Lucy Zoria, 24

Production Assistant, Kyiv

![]() I've always been interested in the history of my mother's parents and grandparents. Their lives give you an idea of what it was like to be a member of the intelligentsia in Soviet times.

I've always been interested in the history of my mother's parents and grandparents. Their lives give you an idea of what it was like to be a member of the intelligentsia in Soviet times.

My mother came from a family of Polish Jews who were originally from Odesa.

My great-grandmother, Selena Shvartzman, grew up in a prosperous, very warm family. Her father was in the oil and gas business. She was an actress, and a bit of a character. We have a lot of pictures of her just posing in different fabulous outfits, and we still have one of her fur coats in a closet. I think she had fun.

Selena Shvartzman Pekker in an array of beachwear, Baltic Sea, 1930s

She got pregnant with my grandmother, Asta, after having an affair with a Russian poet. Who this person is is still a source of great speculation for us.

But she ended up marrying a different man, Hryhoriy Pekker, a cellist who became one of the first Soviet musicians to tour abroad. They moved to Berlin in 1929 and seemed to have quite a nice life there.

They left shortly after Hitler came to power. They had ties to the Soviet Embassy, so they managed to avoid persecution as Jews.

![]()

Selena and Hryhoriy Pekker with baby Asta in Berlin, late 1920s

From there, they moved to Moscow. I think the transition was difficult for my grandmother, especially during World War II, because she had spent her early years speaking German and other kids teased her for speaking the language of the Nazis. At some point, my grandmother gave up speaking German altogether. I never heard her speak it.

Hryhoriy's family, all musicians, died during the Leningrad Blockade. That haunted him. From then on, he always hoarded food. He even slept with bread under his pillow.

My great-grandparents were definitely part of the Soviet cultural elite, but never important enough for it to have terrible consequences. Still, there were many things that were difficult for them once they came back.

Hryhoriy faced pressure for being a "cosmopolitan," a person who wasn't sufficiently committed to the motherland, because he had lived abroad. And the fact that they were Jews made everything more difficult. Asta was denied university enrollment in Kyiv because she was Jewish. Eventually someone with connections intervened on her behalf.

It may have helped that my great-grandmother, Selena, remained very popular in social circles. There's a family story that she once met Leonid Brezhnev at a party in Kyiv. He was Ukrainian himself, of course. He saw Selena drink vodka straight and thought, "Wow, what a woman!" Brezhnev took a huge liking to her, and even helped her and Hryhoriy secure two rooms in a communal apartment right in the center of town.

I think my grandmother inherited a lot of her mother's charm. She was the kind of person who had friends for life.

![]()

Asta Pekker with admirers in Kyiv, 1950s

Her upbringing was quite different from that of my grandfather, Anatoliy Sumar. His father was a commander in the Soviet Army, and he grew up in different countries, wherever his father was stationed -- Romania, parts of Asia.

Anatoliy started becoming interested in painting when he was a teenager. He never really had any formal training, but he read constantly and had a strong theoretical understanding of art history. He particularly loved the Picassos he saw in Moscow. He even named his son Pavlo, the Ukrainian version of Pablo.

He liked to learn on his own. He studied architecture and civil engineering at university, but he never even got a diploma, because he had grown a beard and refused to shave it off. The university wouldn't give him his degree as long as he had the beard. He was very stubborn that way.

![]()

Anatoliy Sumar, "looking very young and handsome and like an impressionist painter,"

according to his granddaughter

My grandparents met at the Philharmonic here in Kyiv. My grandfather used the artist's traditional line: "Let's meet again and I'll paint you!" They got married pretty quickly. It was quite scandalous at the time because she was older than he was and pretty old to be unmarried in the first place. She was 28 and he was 22. But it worked out.

Anatoliy liked to paint the things around him -- street scenes, windows, plants, street lamps. In 1962, he was included in an exhibit of works by young artists. The head of the Ukrainian Communist Party visited the exhibit and singled out my grandfather as an abstract expressionist.

This was usually enough to kill an artist's career, but my grandfather didn't mind. He was ready to give up painting at that point anyway. He went on to hold other jobs in architecture and design. He really only painted for a total of about six years.

But being singled out by the Communist Party boss really contributed to his fame. People started dropping by Anatoliy and Asta's apartment to meet The Artist. He was a very severe person; he didn't like attention. But my grandmother was very hospitable. She was a literary editor and very well-read. They never locked their doors. People would drop by to see him but end up staying because of her. The painter Tetyana Yablonska came, the poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko.

![]()

Anatoliy and Asta, Kyiv, late 1950s

Anatoliy started painting again in the 1990s and had his first exhibit in decades. I think it was only then that he finally understood that his art had a larger meaning. He died in 2006; Asta died in 2012. I feel that these are people who were greater than I am; I'm just here to keep their stories.

I spent some years growing up in the United States, but I really feel at home in Kyiv. It's where my grandparents lived, where my parents live.

Life is harsher here, but there is an openness, a connectedness that you don't see in other places. People put a priority on friendships, on free time. Before Maidan, people thought in terms of when to leave and where to go. But now people are starting to believe they have a future here.

Volodymyr Balega, 60

Photographer, Uzhhorod

![]() Everyone in this part of Ukraine has some Hungarian roots. My grandfather, Yuriy, always spoke Ukrainian, but his name -- Kuruc -- was clearly not Ukrainian. My mother remembers being sent to see her aunts in the summer, and they always spoke to her in Hungarian.

Everyone in this part of Ukraine has some Hungarian roots. My grandfather, Yuriy, always spoke Ukrainian, but his name -- Kuruc -- was clearly not Ukrainian. My mother remembers being sent to see her aunts in the summer, and they always spoke to her in Hungarian.

My mother grew up in a two-room farmhouse with a straw roof. My grandfather bought the house in another town and had the entire thing moved to their village, Kolchyno. They kept pigs, chickens, and livestock.

I was born in that house; I remember it perfectly. It was a perfect example of the old farmhouses you see in Transcarpathia. A few years ago, a museum even offered to buy it from our family to put it on display.

![]()

The Kuruc family outside their farmhouse in Kolchyno, 1930s. Volodymyr Balega's mother, Varvara, is holding flowers and standing to the left of her father, Yuriy, who later hanged himself. Her brother Mykhaylo is far left, front row. Brothers Petro and Yuriy (top row, first and second from right) both died under suspicious circumstances in Czechslovakia.

My grandmother ended up having seven children over 25 years -- six boys and one girl, my mother, Varvara.

World War II was hard on my family. One of my uncles, Mykhaylo -- Misha -- faked his age to enter the army when he was just 16 or 17. He died a month later when he was shot by a sniper in Czechoslovakia.

Two of my older uncles, Petro and Yuriy, went on to train as Soviet intelligence agents. At least one of them studied in Moscow, but since they had grown up in this part of Ukraine, so close to so many borders and languages, they were always going to come under scrutiny.

At some point, Yuriy disappeared. Soviet agents came to Kolchyno to look for him; they suspected him of working for Hungarian intelligence. They didn't find him. He was hiding in a crawl space below the roof of the barn. But the agents interrogated my grandfather brutally, beating him with metal rods.

My grandfather didn't say a word, but he was horrified by their viciousness. I think he just couldn't believe that people could act like that. He hanged himself the same night.

![]()

Petro Kuruc with his daughter, nephew Yura, and mother, Brno, Czechoslovakia, 1950s

Yuriy went on to work with the Czechoslovak special services. He lived in Brno and married a Polish woman; they had a son, also Yura. But it was rumored that Yuriy was providing intelligence to both the English and the Americans. This was at the start of the Cold War.

He ended up dead -- thrown from the balcony of his fifth-floor apartment. His wife died under mysterious circumstances the same year. Little Yura went to live with my other uncle, Petro, who was also living in Brno and also working for the Czechoslovak special services.

Petro was killed in the 1960s or '70s. A car drove up on the pavement and hit him as he was walking on a sidewalk. Everyone assumed it was a deliberate assassination by the Czechs, because he was considered loyal to Moscow.

My family members tracked down Yura only a few years ago. He lives outside of Prague, just leading a normal Czech life. When we first approached him, he thought we wanted to ask him for money.

![]()

Yuriy Balega in his traditional Ukrainian vyshyvanka, 1960s

My father, Yuriy, was brought up in an extremely poor family. When he came to university, he didn't even have a winter coat -- that's how my mother noticed him the first time. A shivering guy eating free bread and mustard in the university cafeteria.

He ended up becoming a very respected professor of history and Ukrainian literature here in Uzhhorod. You had to be a member of the Communist Party in those days to get a high-ranking academic post, and my father was, but he still insisted on having his official picture taken wearing his Ukrainian vyshyvanka instead of a collared shirt, which was considered pretty rebellious. He got away with it somehow.

He's not a healthy person -- he had his first heart attack when he was 28 years old! -- but he's still alive.

![]()

Yuriy and Varvara Balega at opposite ends of the table, with some of her students in between

My mother was a very pretty, popular woman. She was always being asked to be the witness at her friends' weddings because she had nice clothes and looked good in photographs. I have dozens of pictures of her at other people's weddings.

She became a teacher and worked with girls who lived in an orphanage. Her students really loved her a lot.

Several members of my family became alcoholics, and my mother was one of them. Eventually she had to give up her job because her drinking got out of control.

She was very good at hiding it; it took a long time for my father to find out, even though as a little boy I knew. It went on for years. She ended up divorcing my father.

![]()

Varvara Balega with her sons Yuriy (left) and Volodymyr. Yuriy Balega is now a prominent astrophysicist and heads the Nizhny Arkhyz telescope facility in Karachayevo-Cherkessia, Russia.

My wife was studying at that time to become a doctor, and I persuaded her to focus on narcology. We helped my mother quit. She's in her 80s now and she hasn't had a drink in 30 years.

She had a whole second life. She had always had bad asthma and allergies, so finally we moved her to Crimea. The air there helped her immediately, and she ended up getting married again, to a Russian man who fell head over heels in love with her.

My father got remarried, as well. For a while, my parents had the same address -- I mean, different cities but the same street name, the same house number, the same apartment number.

My mother's since moved back to Transcarpathia. Her husband died and, of course, Russia started making trouble down there. I'd go and fight them today, if I could.

![]()

Solomia's daughter is also named Solomia. She's a little shy.

Solomia Lebid, 42

Engineer, instructor in math and computer science, Lviv

![]() I've spent a lot of time collecting family pictures and documents. There seems to be a global tendency to eradicate history, but it's important for me to remember that my family members existed.

I've spent a lot of time collecting family pictures and documents. There seems to be a global tendency to eradicate history, but it's important for me to remember that my family members existed.

My great-grandmother, Maria, was still alive when I was born, but I never met her. She emigrated to the United States in the late 1930s, to avoid the war.

![]()

Solomia's great-great-grandmother Maria Romaniak (left) and her daughter, also Maria. Both are dressed in the traditional clothing of the Boyko villagers who lived in parts of Galicia in western Ukraine.

Maria's daughter, Myroslava, was my grandmother and a very important person in my life.

She grew up mainly in the town of Drohobych and served as a teacher as part of Prosvita, the system founded in the 19th century in Lviv to preserve Ukrainian culture and education.

I still have her school records, so I know that she studied Polish, Latin, Greek, German, math, literature, dance, and nature. When I was growing up and grumbling about science classes, she always told me to stop complaining because as a girl, she had never had the chance to study physics or biology.

Eventually she moved to Lviv. She had hoped to study design in Lyon, but then World War II broke out. She was a very talented seamstress and taught sewing and embroidery classes. For years, she kept the things her students had made for her. They really loved her a lot.

![]()

Myroslava Vesela (second from left) and her students showing off their embroidered handiwork

One time, my grandmother was asked to design outfits for female athletes in Galicia to wear in regional sports competitions.

Up until then, women had been wearing long skirts to play basketball and volleyball, and even for short- and long-distance running. Obviously it was really heavy and uncomfortable, and they asked my grandmother to make something more convenient.

First she designed a skirt with trousers underneath, but even that was too heavy. So eventually she just made trousers for all the women, and then she even made short pants.

This caused a big scandal in the family. Her mother was so disgusted that she stopped speaking to her for two years.

![]()

"These are two neighboring kids who came over to play with my grandmother's dog. I love this picture because you can still see little holes from the tracing wheel she used with her sewing patterns.

She really liked to take pictures, but I guess sometimes she left them lying around when she was working."

During World War II, she continued to teach. She showed her students how to design clothes and recycle old dresses and shirts into new articles of clothing, so that nothing was wasted.

World War II was really hard on my grandmother, though. She was a prominent member of the local community, and this meant keeping track of everyone who was disappearing or being killed or thrown in jail. Poles, Ukrainians, Jews, professors, priests.

Whenever she could, she tried to get people out of jail. Some of them were so grateful they kept in touch with her for the rest of their lives. But she was haunted by the thought of all the people she hadn't been able to help. Sometimes she woke up screaming.

![]()

Myroslava and Ivan with Solomia's father, Yuriy, bundled in rabbit fur

In her personal life, at least, I think she was happy. Her husband, Ivan, was a lawyer. They raised me when I was little, in Lviv. In her papers, I found a note he had written to her: "I love my Myrosia with all of my heart."

![]()

"This picture is of my great-grandmother's cousin and her family. They ended up leaving for Poland, I think."

I love my grandparents very much, and anything that belonged to them is very precious to me. Even a cousin of my great-grandmother is important.

People in Lviv have distrust built into their DNA. Too much has happened in our history. So they distance themselves -- they just sit back and watch and wait for the moment when they will finally act. But that mentality is changing. Slowly.

Andriy Sholtes, 41

Writer, Uzhhorod

![]() I'm an Uzhhorod native; my family has lived here for four generations. My grandparents spoke Hungarian, and my parents and I do, too. It's traditional to teach it to children here while they're young, because it's a difficult language.

I'm an Uzhhorod native; my family has lived here for four generations. My grandparents spoke Hungarian, and my parents and I do, too. It's traditional to teach it to children here while they're young, because it's a difficult language.

I went to a Ukrainian school, but I was also perfectly comfortable socializing in Russian and Hungarian. And I want my sons to speak all of those languages as well. Here it's normal to speak three or even four languages.

![]()

Andriy during dance lessons at school, late 1970s

My grandparents used to joke that if you lived long enough, you could live in five different countries without ever leaving your village: the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, the U.S.S.R., and Ukraine.

My grandparents always spoke fondly about the Czechoslovak and Hungarian periods. I don't think that necessarily means that those were the best times. I just think people's fondest memories are always tied to when they're young.

![]()

Andriy talking to guests during his birthday party

We always traveled a lot, to Hungary and Czechoslovakia. We had relatives there and it was just normal.

The war in eastern Ukraine is real for us -- a number of guys from here have been killed in the fighting. But I've never been to the east. It still feels far away.

The psychological distance between Transcarpathia and the east is really big, but that's normal. We're just our own region. We have our own advantages and disadvantages.

I started university just as the Soviet Union collapsed. But it took a couple years before you could actually feel it.

Things stayed the same for a while -- the people were still Soviet, the buses were still Soviet, there were still statues of Lenin everywhere.

The Soviet way of life didn't have a huge impact on us here -- my parents weren't Communist Party members, but they still had jobs and didn't face any particular problems besides long lines and shortages. There just weren't many opportunities for advancement -- that was the main problem.

![]()

Andriy (far right): "I think we might be drinking Zhigulyovskoye here. You just bought whatever beer was in the store."

A lot of my friends had been brought up in a fully Hungarian environment -- Hungarian schools, TV, newspapers, culture.

Then when they graduated and entered the real Soviet world, many of them were at a disadvantage, not knowing how to adapt. So in the 1990s, a lot of them left for Hungary. Some did OK, some not.

I don't think external circumstances always determine whether you succeed or fail -- it also has to do with the kind of person you are.

But I have no plans to leave Uzhhorod. I like it here. As long as my children are healthy, the war ends, and my book gets published, I'll have everything I want.

![]()

Andriy on a fishing trip in the early 1990s. "We had animals following us around the whole time. Some dogs ate our salo and bread, a bunch of geese dumped my cigarettes in the river, and a cow stepped on my fishing rod and broke it. We still managed to catch some fish, though. In this picture, I think I'm looking at some extra fish we had caught to take home, prior to our departure and prior to their death.

Twenty is a cruel age."

'A Country to Call Their Own'

Volodymyra Kachmar, 54

Architect, Lviv

![]() I was one of those people who never paid attention to history in school -- it was just a form of Soviet indoctrination, and it wasn't interesting at all. But when I started to research my family, I suddenly found history very interesting. I had to start from scratch, but at least I got to choose what I was learning. In 2009, I published a book on my family tree.

I was one of those people who never paid attention to history in school -- it was just a form of Soviet indoctrination, and it wasn't interesting at all. But when I started to research my family, I suddenly found history very interesting. I had to start from scratch, but at least I got to choose what I was learning. In 2009, I published a book on my family tree.

My ancestors were all priests, teachers, and farmers, and like many Galicians, they were stuck between Orthodox Russians on the one side and Roman Catholic Poles and Austro-Hungarians on the other.

In 1915, after the start of World War I, Austro-Hungarian authorities imprisoned a number of Galicians who were considered "unreliable." This included my great-grandfather, Hryhoriy Hrytsyk, who was a Greek Catholic priest and very active in the narodovtsi pro-Ukrainian populist movement.

He was sent to the Terezin prison camp in what is now the Czech Republic, and then to the Talerhof camp near Graz, in Austria. He spent two years there.

![]()

Stefania Hrytsyk, dressed for a cultural performance, Rostov, circa 1916

My great-grandmother, Maria, had no way to support herself and her children, so she fled to Rostov, where Russian authorities were providing aid to Ukrainian refugees. My grandmother, Stefania Hrytsyk, was around 19 or 20 at the time. It seems like they lived comfortably, all things considered.

After my great-grandfather was released from prison, the family returned to Galicia. My grandmother eventually married Stefan Kachmar, who had served in the war and was also a Greek Catholic priest. That was the way it worked -- older priests married their daughters off to young priests.

These girls were raised in religious households and understood what it meant to be a priest's wife -- the charity work, the social obligations, the proper behavior. Other girls would have found it a struggle to get used to.

![]()

Hryhoriy and Maria Hrytsyk celebrating their 50th wedding anniversary in 1943 in Svyate, Galicia. Stefania and Stefan Kachmar are seated bottom right. Volodymyra Kachmar's father, Orest, is standing top left.

I know for a fact that Stefan was not my grandmother's first love -- that was a man who died on the front in World War I. But they still had a good marriage, Stefan and Stefania.

When the Soviets came to power, they made life very hard for Greek Catholic clergy like my grandfather and great-grandfather. They were constantly under pressure to convert to Orthodoxy, as a sign of loyalty, or to give up religion altogether.

My grandfather had 10 junior clerics under his supervision. It would have been very valuable for the Soviets if he had persuaded them all to convert en masse, but he refused to do it, and in 1946 he was shot by a Russian sniper.

They said it was a stray bullet, but his family knew that it wasn't a random incident. The bullet severed his spinal cord; he was paralyzed and died six months later. My father, Orest, was 15.

My other grandfather, Volodymyr Mysyak, was a lawyer and very active in Galicia's Prosvita cultural movement. He graduated from Lviv University and was working in the city of Lyubachiv, in what is now Poland. After Hitler and Stalin divided up Poland in 1939, Lyubachiv ended up on the Soviet side, and that was the end of my grandfather's work as a lawyer.

![]()

Olha and Volodymyr Mysyak at their wedding, 1933

He went on to work in forestry, but in May 1941 he was arrested. On June 26th he was executed at the Zamarstynovskiy prison in Lviv, along with hundreds of other western Ukrainians, for "anti-Soviet propaganda." His daughter -- my mother, Bohdana -- was 6.

At the time, no one knew what had happened to him. Olha, my grandmother, looked for him at the prison, but so many people had been killed and their bodies left to decompose that she couldn't be sure he was among them. She waited for him for the rest of her life.

It was only in the 1990s that the Ukrainian security services released files explaining what had happened to people like my grandfather. In 2000, he was officially rehabilitated. He was never given a proper burial, but his name is engraved on the wall of the prison.

![]()

Olha and Volodymyr with baby Bohdana, 1935

Both of my grandmothers -- Stefania and Olha -- lived to old age. At one point we all even lived together. There was a 17-year difference in their ages, but they respected each other and got along well, perhaps because their fates were so similar. They're actually buried together.

When my sister and I were growing up, our grandmothers never talked about the past. Particularly Stefania. Her husband wasn't a priest who was shot by the Russians. He was just a "worker who died." She didn't want us to be compromised by our family history.

My sister and I were baptized, but we never went to an actual church. Our schoolteachers were assigned to watch the churches on holidays to see if any of their students went in. We didn't want to be reported.

![]()

Bottom, left to right: Volodymyra Kachmar, Olha Mysyak, Stefania Kachmar, and Volodymyra's sister, Oleksandra.

Top: Bohdana and Orest Kachmar

Every branch of my family has people who were killed or imprisoned or forcibly resettled in the 1930s and '40s. All they ever wanted was a country they could call their own.

I can't say I have any hatred toward Russia, but they never saw us as a real nation. They stole our history, and now they're trying to steal it again.

![]()

The hallway outside Lilia's top-floor apartment is covered in mosaics she crafted from CDs, bottle caps, and stones and beach glass brought from summers in Crimea. She was furious when one of her neighbors stapled a satellite cable over one of her creations. "Animals!"

Lilia Bigeyeva, 55

Violinist, composer, Dnipropetrovsk

![]() I'm a mix of Tatar, Ukrainian, and Russian -- the secret formula for very voluble, artistic types. I'm a person of big emotions.

I'm a mix of Tatar, Ukrainian, and Russian -- the secret formula for very voluble, artistic types. I'm a person of big emotions.

My great-grandfather was Musa Bigiyev, a Volga Tatar who was the first person to translate the Koran into Tatar. (My name is spelled slightly differently.) He promoted a very modern form of Islam. He believed in education for women, and he and his family always dressed in European-style clothing.

![]()

Musa Bigiyev (center) with his family

He was friends with Lenin and he worked with the Bolsheviks. He even served as the first imam at the St. Petersburg mosque. But after Lenin died he was basically driven out of the country. He died in Cairo.

Another one of my great-grandfathers was an Orthodox priest in Ukraine. He was sent to a prison camp in the 1930s and never heard from again.

There are a lot of photographs of my Tatar great-grandfather, but absolutely none of my Ukrainian great-grandfather.

One of Musa Bigiyev's sons, Akhmed, was married to my grandmother, Tatyana Volodina, who was an extremely talented Russian pianist. They lived in Russia, in Vologda, but when the repressions started against Musa, Akhmed was thrown in jail. That's how it was done -- the whole family had to suffer.

Tatyana was seven months pregnant at the time, and she knew what it would mean for herself and her children to be related to an enemy of the regime.

![]()

Tatyana Volodina. Lilia's father, Iskander, is on the right.

She was very lucky to have a friend who worked at the marriage-registry office, which also registered divorces. Her friend was able to change a document to make it look as though Tatyana and Akhmed had gotten divorced.

It didn't make his family very happy. But I feel like she had to do it, to save herself and her two sons. The Soviet system forced people to make very desperate decisions sometimes.

Tatyana took her children and moved to Ukraine. She was an amazing pianist and composer and performed her entire life, up until she was 85. She had incredible hands. I think I have her hands.

![]()

Lilia's mother, front and center, Melitopol, 1940

My mother was born at a time when a lot of children were getting idiotic names like Nenil and Traktorina. But she was named Aelita, after the great science-fiction novel by Alexei Tolstoy. People usually just called her Alla.

This picture was taken at the start of World War II; that's probably why the children are wearing military costumes. Melitopol was occupied by the Germans and saw a lot of destruction. It's possible some of these children weren't alive a year later.

I was born in Melitopol, raised in Zaporizhzhya, and have spent all of my adult life in Dnipropetrovsk. It hasn't been easy, this past year in Ukraine. The loss of Crimea is a tragedy, the war is a tragedy. And it's far from clear that our government and our people are really prepared to institute rule of law.

But I would never consider leaving Ukraine. One of the reasons is my Uncle Leonid.

His father was the Orthodox priest who disappeared in the labor camps. Leonid was arrested during World War II, and as soon as he was released, he left for the United States. He lived there for 10 years, someplace in Ohio -- we don't even know where. Sometimes he sent pictures.

![]()

Uncle Leonid, somewhere in Ohio

From all appearances, he lived well. He was an economist and he rented a room in a house with a television that was enormous, by our standards. But as soon as he had the possibility to come back, he did it without hesitation.

We barely had indoor plumbing at the time, let alone gigantic televisions. But he never regretted it. He told me a story about his American landlady borrowing a dollar from her son and the son charging interest when she paid it back. Leonid told the story without any particular emotion, but to me it was horrifying.

![]()

Iskander and a colleague, wearing fake noses, Zaporizhzhya, 1960s

People think there was no laughter behind the Iron Curtain, but there was a lot! My family was always dressing up in costumes, putting on performances.

That's how we celebrate birthdays even now. I don't need jewelry or some kind of name-brand cognac; I just want my friends to come over and say, "What kind of nonsense are we going to get up to tonight?" We put on little plays, we sing, play music.

My parents both worked at the Zaporizhzhya Abrasive Plant, a huge factory at the time, and they were active in humor competitions and performances put on by the staff. We always had crowds of people over at our house rehearsing. It's funny to hear experts now talk about how to boost morale at work.

![]()

Lilia as a little girl. "I never got my ears pierced, and I don't wear rings.

When you play violin, jewelry just gets in the way."

Every member of my family studied music or dance in some form. It helps you unlock your creative side, even if you end up doing something completely different.

I started playing the violin when I was 7, and I started composing when I was 13. I've spent many years as a music teacher as well.

I've seen a lot of my pupils grow up and become professional musicians. Others go on to other jobs but still enjoy playing music; others give it up completely and never look back.

The war is very close to us, here in Dnipropetrovsk. Every day there's bad news. But we continue to play music, my pupils and I. Culture and art, these are the things that have always helped us through frightening times.

![]()

Lilia Bigeyeva (back row, center) with her pupils, 1980s. "Children today seem too busy. To study music, you really need to be calm."

My grandfather always wanted to write our genealogy. So when he died, I decided to do it for him.

My grandfather always wanted to write our genealogy. So when he died, I decided to do it for him.

I'm Ukrainian-American, but I moved to Ukraine a few years ago. Lviv used to be my ancestral home. Now it's my permanent home.

I'm Ukrainian-American, but I moved to Ukraine a few years ago. Lviv used to be my ancestral home. Now it's my permanent home.

Everyone in Ukraine has an interesting history. I've researched so many families -- my own and other people's -- and it's always fascinating.

Everyone in Ukraine has an interesting history. I've researched so many families -- my own and other people's -- and it's always fascinating.